You know all those moments in which the prince--or the monster--or the monster prince-- falls asleep with his head on the princess's lap?

In the original version of the story, she's lousing him.

Yep.

Lousing.

As in "head-lice".

Ah, the romance.

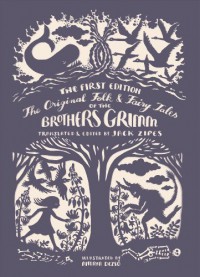

You may think you know Grimms’ Fairy Tales, but if you’ve been reading them in English, I can guarantee you’ve never encountered them like this, as Zipes' book is the first time the original manuscript has been translated into English. After the disappointing reception of their 1812/1815 "Volk tales," the Grimms concluded that the stories were too coarse and unfinished and began to edit them. In each subsequent edition, culminating in the so-called "definitive" 1857 version, the stories were a little more flowery and overblown, a little more bowdlerized, a little more pious and inoffensive to the readers of the day.

In this book, Zipes has rendered the stories in the raw, unvarnished, dialectic form, just as they were originally transcribed by the Grimms. In this form, we see the digressions into rhyme or extraneous detail, the nonsensical, often fragmented plots, and the sometimes tiresome repetition of themes and plotlines, but we also get the closest glimpse of the real stories. The differences between the versions are as fascinating as the stories themselves. Fortunately, Zipes spends quite a significant portion of the introduction contrasting the tales and highlighting the differences. (Sadly, in my advanced reader copy, the text of the appendix was so garbled and scrambled that I was often unable to understand the commentary. I was, however, able to read enough to appreciate Zipes' thorough commentary and to wish that the appendix had been complete.)

So, apart from the romance of lousing, what did I learn from the original Grimms' Fairy tales?

The myth of the wicked stepmother.

The wicked stepmother is also far more of a creation of the Grimms than a true artefact of the stories themselves. In the 1812/1815 version of the tales, it is the biological mother who tempts Snow White with a poisoned apple and sends Hansel and Gretel into the forest. However, because the Grimms believed in the sanctity of motherhood, those less-than-ideal maternal examples were quickly transformed into the wicked stepmothers we know and love.

The birth of the witch.

Most of the powerful women in the 1812 version are transformed from fairies, queens, and saints into the ubiquitous witches of the 1857 version. Indeed, this preference is clear even in the 1812 version: in “The Fisherman and his Wife," a wife's greed cannot be satisfied, not with a new house, not with the whole kingdom, and not even with becoming king and pope. Of course, a woman seeking such exalted (and inherently masculine) positions must be punished by the end of the story, but is interesting that although the Grimms note that there are many versions of the story that feature a rapacious husband, they chose the one with the avaricious wife. And indeed a major theme of the stories with princesses as protagonists is a "taming of the shrew" in which the proud woman is humiliated into her proper place.

Ah, the romance.

As fairy tales have been reshaped and retold, they have gained in sensibility and romanticism, so that the original versions come as something of a shock. One of my favourite altered stories is that of "Rapunzel". In the 1857 version, the half-witted Rapunzel blurts out that the prince climbs up her hair far faster than the evil witch. In the original story, the prince gives Rapunzel rather more than passionate glances until Rapunzel’s clothes start...ahem...fitting rather tightly around her stomach, causing the fairy to cast out her “godless child.” And Snow White isn’t saved by a kiss; instead, a servant exasperated with cleaning the glass case eventually slaps her, accidentally performing some variant of the Heimlich maneuver and causing the chunk of apple to fly out of her throat. (Life lesson, Snow White: when offered a magical apple, chew, don’t gobble.)

The morality of the tale.

If it is the case that “good” always triumphs in fairy tales, then “good” had a rather peculiar definition in 1812. In quite a few of the tales, the only moral of the story seems to be that "might is right." Several of the protagonists are gleefully cruel, vindictive, and violent, and it is only these less-than-kindly actions that lead to a happily-ever-after. For example, in "The Frog Prince," it requires parental pressure for the princess to grudgingly fulfil her bargain with the frog, and even then, when the frog petitions to sleep in her bed, she tries to kill him by throwing him against the wall, causing him to turn into a handsome prince, at which point she does indeed promptly take him into her bed.

Even "Beauty and the Beast" takes something of a hit: a father goes to town and offers to get each of his three daughters a present of her choice. The first two ask for something apparently outrageous--gold, jewels, etc--whilst the youngest asks for something apparently humble and simple, like a rose or a singing lark. Unfortunately, she asks for her gift in winter, making it the most unreasonable request of all. The father finds a garden and tries to get her gift, runs into a beast, and has to give up the first thing to greet him, which always turns out to be the self-same youngest daughter. In several of these "beast-bridegroom" tales, she tries to avoid her responsibility by sending another woman in her place, but the beast always detects her chicanery.

Slap a cross on it.

The injection of Christian piety is often superficial at best; for example, in one of the stories, the Virgin Mary takes on a role that seems more suited to a fairy or pagan goddess, making a deal with one woman for her newborn child and punishing another by repeatedly spiriting off her children into a palace in the clouds. The devil takes the place of the giant in the Jack-and-the-beanstalk stories, complete with sympathetic wife. One of the most amusing such tales was one in which three journeymen make a deal with the devil that they will answer all questions with “All three of us,” “For money,” and “That’s all right.” (Yep, I’m sure that will turn out well.) The most problematic of all the stories is "The Jew in the Thornbrush," a tale featuring an “upright” Christian punishing an “evil” moneylending Jew. The Grimms note in the appendix that they found several versions of the tale, but as the original features a "thieving monk," they appear to have invented their antisemitic version.

In this original form, the collection is somewhat difficult to read, as the stories are often fragmentary and repetitive. (In fact, some point, I'd like to put together a sort of fairy-tale MadLib to cover the majority of the stories.) The collection contains a smattering of "just so" stories, a few of the Epaminondas style, and even some possible origins of Pinnochio and the phrase, "Open Sesame." Most of the stories have a similar theme: a protagonist who is virtuous, but makes a mistake, and must fulfil a series of nearly impossible tasks to achieve redemption. Not all of the stories end happily; for example, "The Twelve Dancing Princesses" had a less uplifting ending than the better-known version, but in general, things turn out well for simple or innocent protagonists. Yet the stories contain that intrinsic charm that only fairy tales possess. Good deeds are guaranteed to produce tangible rewards, so they can be performed not out of kindness but because of an expectation of karmic payback. One should always follow the edicts of a mysterious man or woman in the woods, no matter how insane the commands might be. Everything can be set aright without explanation; a prince or princess can be restored to life, a marriage to a less desirable woman can be nullified without question, a child can be found and restored, a curse can be instantly undone. Evil is obvious and evildoers can be destroyed without mercy. Overall, although this wasn't perhaps a particularly absorbing read--the sheer amount of repetition made the stories quickly tiresome--I greatly appreciated the opportunity to see the stories in their most unvarnished form.

~~I received this ebook through NetGalley from the publisher, Princeton University Press, in exchange for my honest review. ~~

15

15