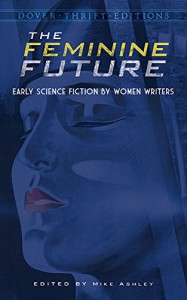

The Feminine Future

edited by Mike Ashley

When I saw an anthology of early female-authored scifi on Netgalley, I knew I had to grab it. While I’m well aware of the female participants in the golden age of detective fiction, I had no idea that women were also so active in early science fiction. All the stories are in the public domain, but I think the stories are more approachable here, as Ashley starts each story with a short biography of the author. Ashley has compiled an interesting collection: most of the stories were written before the turn of the century through the first war, at a time in which science and technology were radically transforming everyday life. Perhaps because of this, the common theme in most of the stories is the threat of technology. Almost every story treats technological advancement almost biblically, as the fruit of forbidden knowledge: an advancement that raises humanity too close to God and inevitably leads to disaster.

The other fascinating aspect, to me at least, was the predominance of the male perspective. Ten of the fourteen stories feature a male protagonist and narrator. The remainder constitutes a male narrator but female protagonist/storyteller, a female following her scientist father, a female narrator captured by a creepy serial killer, and and an omniscient perspective that focuses mainly on the female characters. This last, “Divided Republic--An Allegory of the Future” by Lillie Devereux Blake, is so outspokenly and rather absurdly pro-feminist that it could have been written by Ariadne Oliver, Mrs. Rachel Lynde, or Amelia Peabody. Written in 1887, it neatly predicts both the initial rejection of suffrage and the legislation and subsequent failure of Prohibition, at which point the women go on strike and start their own county. It’s an entertaining little tale, but also rather problematic. Even as Blake agitates for equality, she strongly stereotypes the sexes into rigid and restrictive gender roles, casting women as the docile peacemakers and men as sinful, noisy, and active.

“Friend Island” by Francis Stevens is not much more subtle, but far more interesting. It features a world where “woman’s superiority to man” has been recognized and women hold all the powerful positions in the story. A man interviews a female sailor about her experiences, and she tells him a yarn about a sentient floating island. The gender power dynamics are all the more interesting because they aren’t the focus of the story itself.

“The Painter of Dead Women” by Edna W Underwood, on the other hand, is a critique of the gender norms of the time. The only story in the collection completely narrated by a woman, it explores society’s obsession with female beauty. As one character puts it,

“Death … is the thing most to be desired by beautiful women. It saves them from something worse--old age. An ugly woman can afford to live; a beautiful woman can not. The real object of life is to ripen the body to its limit of physical perfection, and then, just as you would a perfect fruit, pluck and preserve it. Death sets the definite seal upon its perfection.”

The story itself is classic horror, with a twist that was viscerally reminiscent of Gunther von Hagens’ exceedingly creepy Body Worlds.

The last story involving a female narrator, “Via the Hewitt Ray” by M. F. Rupert, is more a classic adventure story that reminded me quite a bit of Wells’ Time Machine. A (male) scientist travels to another dimension via his invention of the eponymous Hewitt Ray. After he disappears, his worried daughter sets off to rescue him. In the other dimension, she meets several different races, including one ruled by women, and finds herself in the middle of a bitter conflict between the different races. I had trouble interpreting Rupert’s feelings about the society she creates; the female protagonist is horrified by the dominant females' treatment of men and seems not to mind her “kindly” father’s patronizing attitudes to her. At first, I thought the story was going to be a commentary on tragic misunderstandings due to physical differences, and was rather disturbed when much to the contrary, the “happy ending” turns out to involve utterly remorseless genocide.

Every story in the collection, apart from these four, portrays a male protagonist acting within a man’s world. As previously noted, most of the remainder provide a sense of technology as reaching outside of the natural order of things. There are only a few exceptions. The first story in the collection, “When Time Turned” by Ethel Watts Mumford, features a man who is travelling backwards in time. Although interesting, I got very hung up on some of the conflicting details--for example, the narrator comments that he looks to be about 50 when he is suppose to be 23. I can’t imagine how that would work when he turned back into a baby, but an interesting idea nonetheless. “The Great Beast of Kafue” by Clotilde Graves is more fantasy or horror than scifi and involves a mysterious monster in a Zambian lake. The most interesting part of the story, in my opinion, was the biography of Graves herself: even though she lived in the late Victorian era, she apparently often dressed as a man and smoked in public. It is fitting that her story is equally unconventional. “The Flying Teuton” by Alice Brown provides a fascinating portrait of American pacifist view on the Great War. Written before the outcome of the Treaty of Versailles, it postulates rather more forgiving Allies who promote healing in Europe rather than punishment. Unfortunately, the sea is rather less forgiving. It provides an interesting glimpse of rather hopeful views of the time, though I would have called it “The Flying Deutschman.”

The remainder of the stories all deal in technological advancement gone awry, ranging from “Ely’s Automatic Housemaid” by Elizabeth W Bellamy, an amusing little comedy about robotic “Electric Automatic Household Beneficent Geniuses” running amok, to “Those Fatal Filaments” by Mabel Ernestine Abbott, a succinct little tale about how a thought-reading “thinkaphone” can cause more misunderstandings than it cures, to the “Ray of Displacement” by Harriet Prescott Spofford, an odd little story in which the protagonist discovers a new “Y-ray” that can make people invisible and temporarily intangible. Unfortunately for the protagonist, the malice of an old acquaintance leads him to be locked up in prison, where he meets the unsubtly-named chaplain, “St. Angel,” who helps him to utilize his invention to gain his freedom. Some of the stories were ridiculously unscientific, even for the knowledge of the time. The premise of “The Automaton Ear” by Florence McLandburgh is that all sounds last forever, growing fainter as they travel endlessly around the globe. The idea is more romantic than feasible--after all, if every sound is permanent, how does the scientist and his machine manage to capture only a pleasant medley of famous speeches, world-class opera, and birdsong?

Many of the stories involve a quest for immortality. In “The Third Drug” by Edith Nesbit, life and death are inextricably tied, and immortality can be found only in their intersection. I’ve always loved E.E. Nesbit, and was amazed by the difference in tone of this creepy little tale. For me, the most disturbing aspect was the way in which the antagonist twists the Christian doctrine of the talents:

“I have not buried my talent. I have been faithful. I have laid down all--love, and joy, and pity, and the little beautiful things of life--all, all, on the altar of science, and seen them consume away. I deserve my heaven, if ever man did.”

Like immortality, eugenics was a disturbingly common theme in the stories. It is most overt in “Creatures of the LIght” by Sophie Wenzel Ellis, which also happened to be both my least favourite and the longest story in the collection. When the (incredibly handsome, intelligent, and athletic) hero sees the picture of a beautiful woman, he suffers from an immediate, passionate, and reciprocated case of Instalove that pits him against the superhuman outcome of a scientist’s eugenics experiment. (He also immediately decides to dump his good-natured, intelligent, but insufficiently attractive fiance, although I’m not sure he ever gets around to telling her.) The story not only involves a fatuous and ridiculous bit of InstaLove; it also contains a secret laboratory in the Arctic, time-travelling villains, a superhuman seductress, and a Death Ray. The message is as ill-considered as the rest: even though the (incredibly beautiful) characters conclude that “perfection” is not to be desired, the story ends with everyone cheering about how events brought together “a perfect man and a perfect woman” which will have “furthered natural evolution.” Yuck.

The story that stayed with me the longest was “The Artificial Man” by Clare Winger Harris, which explores the relationship between the physical form and the intangible self. After a terrible accident that left him with an artificial leg, the main character sets out to find out “by how slender a thread body and soul can hang together” by replacing as much of his body as possible with artificial parts. Although the message is more dogmatic than we would accept in our age of biomechanical enhancement, I think the idea is as fascinating and troubling now as it was back then. I’m currently reading Richard Morgan’s Artificial Carbon, and was startled by the similarity of the theme: in a world where the physical form can be replaced by computers and machinery, where does the indivisible “self” lie?

Overall, I greatly appreciated the opportunity to widen my knowledge of early scifi. While the stories themselves are dated, they provide an interesting glimpse of another time, a point where, like the present moment, the influx of technology rapidly transformed not only everyday life, but also society’s hopes and fears.

~~I received an advanced reader copy of this ebook through Netgalley from the publisher, Dover Publications, in exchange for my honest review.~~

5

5